The Compass, Time, Measurement and Junks

The compass is one of the four great inventions of ancient China and the example pictured above is an early version from the Han dynasty. Records of the use of lodestones in China for feng shui, also called Chinese geomancy, to align locations in harmony with nature, go all the way back to the 3rd century BC (Warring States period). The devices are simple and are comprised of two parts: a lodestone, which is a naturally magnetized mineral called magnetite, in the shape of a spoon, and a flat bronze plate. Both the bottom of the lodestone and the top of the bronze plate are highly polished so as to reduce the friction between them and to allow the spoon to freely rotate and align with earths magnetic forces and point north-south.

This is a similar model of an ancient compass that also used a magnetized metal scoop on a bronze plate called a Si nan (or south pointer) from the Han dynasty. Ancient Chinese geomancers would shape pieces of lodestone into spoon shapes and use their magnetic properties for divination. The metal spoon has the blunt rounded end point north and the long tail point south. The bronze plate it sits on called a di pan shows characters on it that depict the 8 heavenly stems, 12 earthly branches, 4 divination symbols and 24 locations. This compass was used for over 1000 years until the Tang dynasty.

Rubbing small pieces of iron against a lodestone would magnetize the metal and cause them to line up north-south with the earths magnetic fields. When poked through small pieces of wood they were known as floating compasses. Some metal pieces took the shape of a fish or were embedded into wood and carved like a small fish and know as floating fish compasses. Many of these began to emerge in the Song dynasty and meant that ships could navigate even if they couldn't see the stars or if the sun was obscured by cloudy weather. This was a landmark device for ship navigation.

Another type of compass was the south-pointing turtle which dates to the Yuan dynasty. It consisted of a small piece of wood carved in the shape of a turtel that had a piece of lodestone placed inside. A small iron needle was inserted into the tail until it touched the lodestone. When placed on top of a wooden pedestal the turtle aligned itself with the earths magnetic fields and its head pointed south and tail pointed north.

This version of a compass is called a Luopan and it is mainly used in feng shui to determine the best direction to orient a structure, location or item. The round piece of wood that sits at the center with all the rings of feng shui formulas around it is know as the heaven dial. It rotates freely inside the square piece of wood called the earth plate. Holding it level in the center of a location facing the entrance, the dial is rotated until the needle of the compass lines up with the red wire in the center. The lines that are carved into the earth plate are the directions that the readings are taken.

This is an example of a suspended or hanging compass from the Northern Song dynasty. An iron needle was rubbed against a magnetic lodestone to induce magnetic properties and was suspended by a fine waxed thread or string.

This is a Mariner's compass, it has a steel needle that freely pivots on a pin inside of a hollowed out piece of wood with a wooden lid. The delicate needle is protected by a piece of glass held in place by a brass ring. The chinese characters were carved into the face of the compass and painted white, the character for south is painted in red. Basic compasses such as this were first used aboard junks in the Song dynasty and continued to be used to guide ships all the way up into the 20th century.

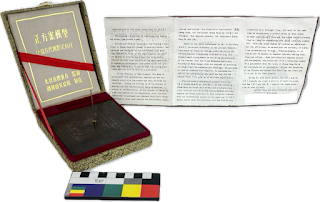

Miniature model replica of the Zheng Fang An. This instrument was used to find direction based on where the top of the shadow of the bronze rod in the center intersects the concentric circles on the bronze plate below at two different times of the day. Drawing a line between these two intersection points helps to determine the east-west line. This instrument was designed by the astronomer Guo Shou Jing and dates back to the Yuan Dynasty.

The earliest reference to the use of candles to tell the passage of time is from a poem by You Jiangu (520 AD, end of the Southern and Northern dynasties time period). A rough model of his candle clock is pictured above and was made of wood and metal with transparent horn panels for the sides. It consists of six wax candles of uniform diameter, each weighed about 112 grams (0.25 pound), and were 30 cm (12 inches) in height with a mark every 2.54 cm (1 inch) along its length. Each mark represented 20 minutes had passed and the candle would completely burn down in four hours. The six candles in total would last 24 hours or one entire day.

Shown here are various forms of incense that are burned in daily life. Incense is typically made from the wood of fragrant trees like Aquilaria (Agarwood), Santalum (Sandalwood) and the inner bark of Cinnamomum (Cinnamon) that are ground into a paste and formed around a bamboo stick. By spacing different incense fragrances along the length of an incense stick one could tell the passage of time by the scent of the incense being burned. The incense used during common religious practices may have less scent or no odor because the smoke is primarily being used to convey the prayers of the person praying to heaven, and not the scent.

A replica dragon incense timer from the Qing dynasty. A long incense stick of uniform thickness would be placed in the metal trough running down the center of the dragon and small threads with weights at both ends would be placed on top at regular intervals. As the incense would burn down it would break the small threads holding weights at both ends and cause them to bang into the metal pan beneath. This would alert anyone listening to how much time has passed.

A replica of a bronze incense burner or hill censer, known as a boshanlu, from the Han dynasty. When burned the incense would escape through the holes in the lid and appear like rising clouds or mist. Some believe that these censers represent the mythical Kunlun mountains, Shangri-La or Mount Penglai, the land of the eight immortals. It is said that on this mountain everything appears pure white, there is no winter, no agony. It is a wondrous place where palaces are made from gold and silver, where jewels grow on trees. It is a place where rice bowls and wine glasses never become empty and there are magical fruits that grow here that can heal any ailment, grant eternal youth and even resurrect the dead.

This is a replica of a gimbal incense burner or bedclothes censer from the Han dynasty. This is the first use of the gimbal in China. A piece of incense would be placed in the central cup and lit then the case would be closed and locked and be placed among cushions and clothes. If the sphere was bumped or rolled the gimbal rings inside would rotate accordingly so as to always keep the incense upright.

This is a miniature equatorial armilla made of bronze. Equatorial armilla were used to measure solar time and the equatorial coordinates of solar objects like stars (specifically right ascension and declination). The actual 17th century instrument this model is based off of is over 3 meters tall and is found on top of the Beijing Ancient Observatory. This observatory has maintained the longest continuous observation records among all of the existing observatories in the world. Instruments like these helped astronomers with their observations for the Emperor. Since he was considered the Son of Heaven, tracking the movements of the heavenly bodies was a very important task to him and was known to be closely tied to the destiny of his rule.

A model of the escapement water wheel that powered gears that turned an armillary sphere (shown) that was inside of a large astronomical clock tower created by Su Song during the Song dynasty. The original water wheel was 3.7 meters (11 feet) in diameter and had 36 scoops that would fill up one at a time with water at a constant rate. This was one of the earliest forms of an escapement mechanism in a clock.

Efforts to better study the weather resulted in an ancient hygrometer or 湿度计. This was invented in the Shang dynasty to help measure the amount of humidity in the air. In this model a known weight was placed on one side and on the other was a bundle of charcoal. In more humid environments the charcoal would absorb the moisture and the charcoal bundle would be weighed down. In dryer environments the charcoal would not absorb as much and weigh less and be lifted higher.

A wooden abacus called a suanpan that used dried insect galls from a tree to make the counting beads. Note that some galls have desintegrated, there should be two beads in each top column and 5 beads in each bottom column. Each top bead has a value of 5 and each bottom bead has a value of 1. For example, the beads pictured hear equal 9 (one top bead was moved down and four lower beads were moved up). Now if we move one top bead from the second column down we get a value of 59, now move one top bead from the third column down and we have a value of 559, etc. It is possible to add, subtract, multiply and divide on a suanpan.

This is a replica of the worlds oldest decimal multiplication table called the Suanbiao from around 305 BC (during the Warring States period). It consists of 21 bamboo slips, each about 7-12 millimeters wide and about half a meter long and tied together with hemp. Amazingly the calligraphy that was brushed onto the slips can be used to calculate numbers up to 99.5.

Two bronze replica measuring instruments from the Qin dynasty. These were of the type typically used for alloting daily rations of food to Soldiers. The larger instrument measures 1/3 dou (650 ml or 2.75 cups) while the smaller measures 1 sheng (200 ml or 0.85 cup).

A pair of wood rulers measuring 37.3 cm (14 and 11/16 in) and divided into 10 equal subunits marked with brass pins along its length every 3.7 cm (1 and 5/8 in). I believe these were used by tailers to make clothing and other custom clothing items. Beneath them is a modern brass ruler measuring 30.5 cm (12 inches) and divided into 12 equal subunits marked by tick marks along its length every 2.54 cm (1 inch).

A replica pair of calipers made of brass from the time of Wang Mang's rule, Xin dynasty.

This is a small model of one of the first directional earthquake tremor detection devices in history. Called a seismoscope it utilized an inverted pendulum that would fall in the direction from where the tremor was coming from. The pendulum would knock a ball out of the mouth of one of the dragons hanging on the side and into the corresponding toad below it. Whatever toad had a ball in its mouth would indicate what direction an earthquake tremor took place.

This is a model of a south-pointing chariot or south facing-carriage that was made during the Three Kingdoms period. This was a form of directional dead reckoning that used differential gearing to keep the wooden figure on top always pointing south, no matter which way the chariot was pulled. This early navigational tool may have been used in ceremonial practices and possibly some military operations.

A chinese pirate junk showing the characteristic junk rigging with full bamboo battens that go down the sails. The lightweight but strong bamboo battens meant the crew could raise and lower the sails from the deck, kind of like a window blind, without the need to climb the masts. Also, if torn or ripped by cannon fire, the tear would stop at the battens, this would prevent the sails from completely ripping open. Also the shape of the sails with the battens would act as an airfoil to help the ship sail upwind. Ultimately the simple design required less rigging and crew to operate too.

A model of a Ming dynasty ship called a bao chuan (宝船) meaning "treasure ship". Lots of sails were needed to harness the wind to move a heavy cargo laden ship like this that could have been up to 200-250 feet in length. There is evidence of early sticky rice mortar that was used to line the bottom of the hulls of these huge ships to help prevent tortional twisting of the vessel and help them survive on the rough, open ocean.

Model of a type of ship called a sha chuan (沙船) meaning "sand ship", it was also known as a "pechili trader" junk. These ships were made to transport heavy cargo in the shallow waters of the lower Yangtze river. Since there was no keel on flatbottomed junks the leeboards on the sides of the ship could be lowered on the leeward (downwind) side to help the ship track straight, prevent drift and help prevent them from keeling over in heavy crosswinds. Seen hanging on the side of the stern is a large rock filled bamboo basket known as a Tai Pin Lan (太平籃) meaning "peace basket" that can be lowered into the water to serve as external ballast in rough weather.

A model of a dragon boat from the Sui dynasty that would have been used to transport royalty along inland rivers and canals.

This is a view of the stern of a model of a guang chuan (廣船), a type of sea going junk showing a retractable, fenestrated rudder. The diamond shaped holes in the rudder, or fenestrations, lessened the pressure on the face of the rudder so it was easier to steer. In addition, the rudder could be winched up when in shallower waters close to shore to prevent damage.

This is a type of freight junk called a Ma-Yang-Tzu and it was used to navigate the rocky rapids and transport cargo along the upper Yangtze river. This boat has the sails lowered. Tung oil was utilized to treat the hull, decking and woven bamboo matting over the cabin to protect and waterproof the ship. The long yulohs take place of oars, these can be up to 35 feet in length and can propel the boat in slack water. This model has only a single pair of yulohs but a large junk often carries up to a dozen. Although a single crewman can handle one, additional crewman often pitch in to work each yuloh. In total a crew of a ship of this type consists of about twelve men.

This is a model of a Song dynasty passenger ship that was used to transport passengers along inland rivers, tributaries and canals. There were no oars or sails, instead it utilized the current to reach its destination and in very slow areas could be pulled from a rope on shore tied to the mast.

This is a model of a crooked-stern junk used to traverse the dangerous rapids of the Kungt'an Ho of the Upper Yangtze river near Fouchou. Instead of a rudder there is a large stern oar and a smaller oar, both are operated by a person who stands on the scaffold above the cabin. The twisted or crooked-stern allows for the use of both oars simultaneously, operating in different planes, so the person can steer the junk safely through heavy rapids.

A model of a bamboo raft or tray boat that was commonly used in the Formosa Straight (Taiwan Straight). Removeable centerboards could be placed in between the bamboo hull to guide the ship. Often used for fishing or to ferry passengers from ship to shore. First class passengers would sit in the watertight tub and second class passengers would sit on the woven bamboo mat.

A model junk ship with the outer planking removed from the hull to show the watertight bulkheads that go all the way up to deck level. The joints and seams of each bulkhead were typically caulked with a mixture consisting of three ingredients: a native fibrous non-stinging nettle plant known as Ramie or China Grass (Boehmeria nivea), lime and tung oil. If one section was damaged only that section would flood while the rest would be kept dry, this helped to prevent the ship from sinking.

A large piece of bamboo split in half to show the hollow segmented core. This might have been the original inspiration behind watertight bulkhead partitions that were used in junk ships.

A typical raft used by cormorant fisherman on the Lijiang river in Guilin, southwest China, made up of a few large pieces of bamboo that are lashed together. One of the simplest designs. A lamp is often used at night to attract fish to the raft. When a cormorant has caught a fish the fisherman brings the bird back to the boat with a handline attached to its body and has it regurgitate the catch.

Comments

Post a Comment